These ‘coronavirus’ months at home began with feeling anxious. It settled down into a routine, restful at times, restless at others. Gradually, lockdown started to become tedious and I became desperate to achieve something other than domestic chores – all necessary but many of them repetitive, made worse by not much of a change of scene or social encounters. I don’t like long chats on the phone, Zoom was an alternative but ultimately unsatisfactory, so reading and writing, both of them top of my list in ‘normal’ life, enjoyed more and more of my time.

I read ‘Wolf Hall’ some years ago aboard a Turkish gulet, sailing along the Lycian coast. It took me a while to get into it but something suddenly ‘clicked’ and I was on my way. The second book, ‘Bring Up The Bodies’, didn’t need any support from the first. I was already captivated and rushed straight in.

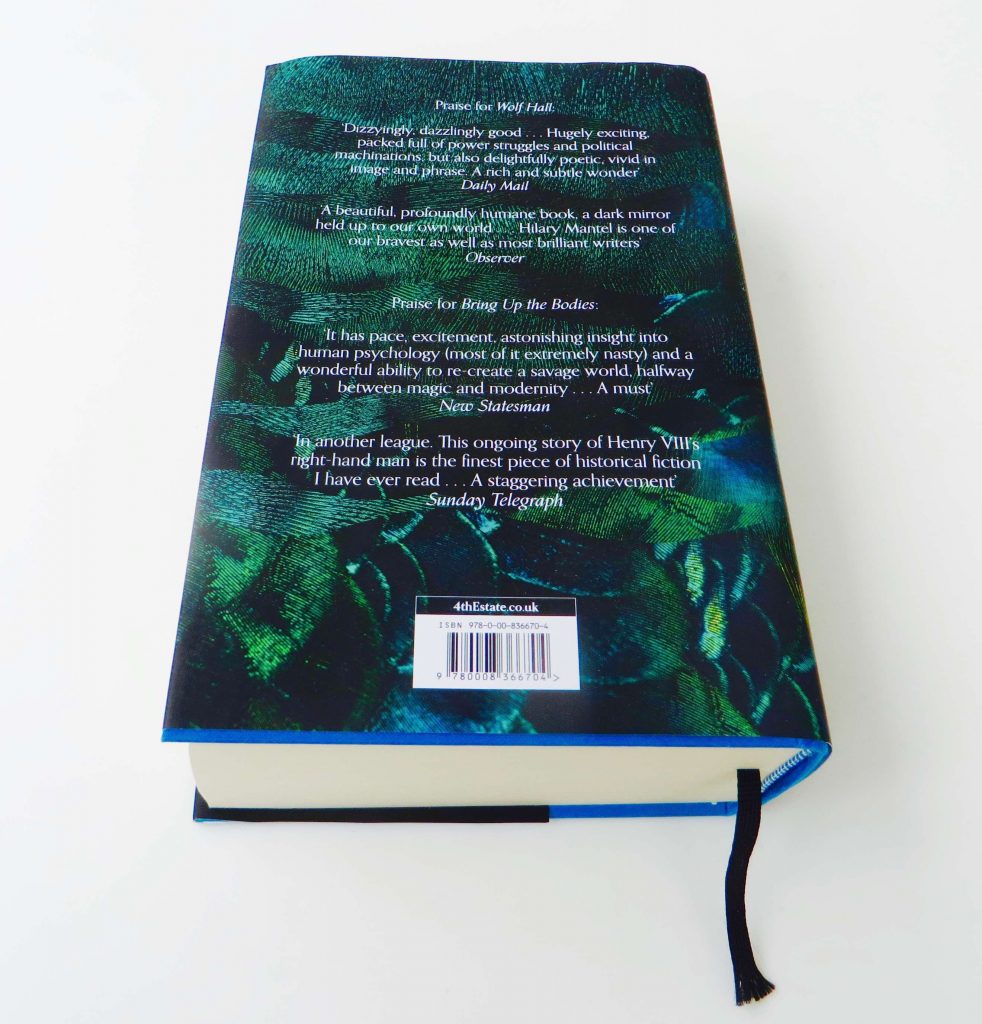

Instead of adding my own comments here, I ask you to read what the critics said about both those books, which are listed at the front of both ‘Wolf Hall’ and ‘Bring up the Bodies’. Many of them are very insightful and I would be surprised if anyone who reads them doesn’t immediately immerse themselves in the books.

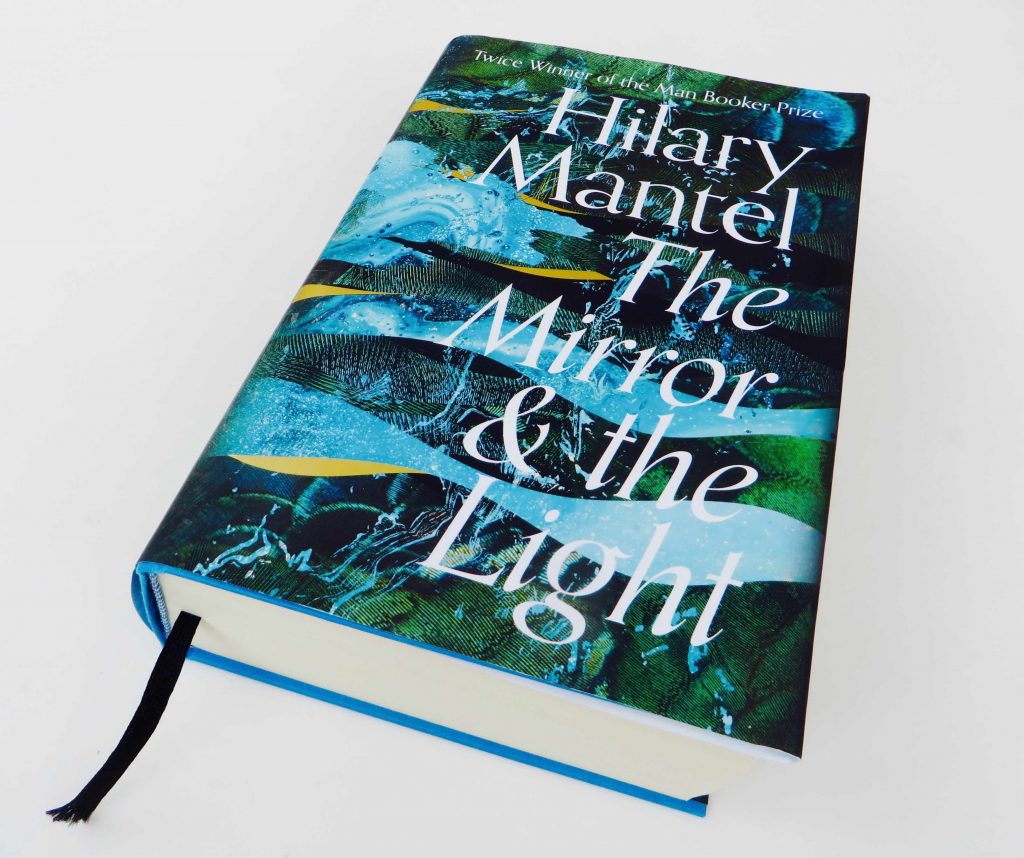

The last part of the trilogy, ‘The Mirror & the Light’, finally arrived and given my own sojourn in the ‘tower’ during lockdown, it seemed to me to be the very best time to attempt the 900 pages confronting me.

Hilary Mantel lists the cast of characters and their connections to one another at the beginning of each book, along with family trees of the Tudors and their rivals. You need to make yourself familiar with all of this before starting to read if you don’t have a good knowledge of English history.

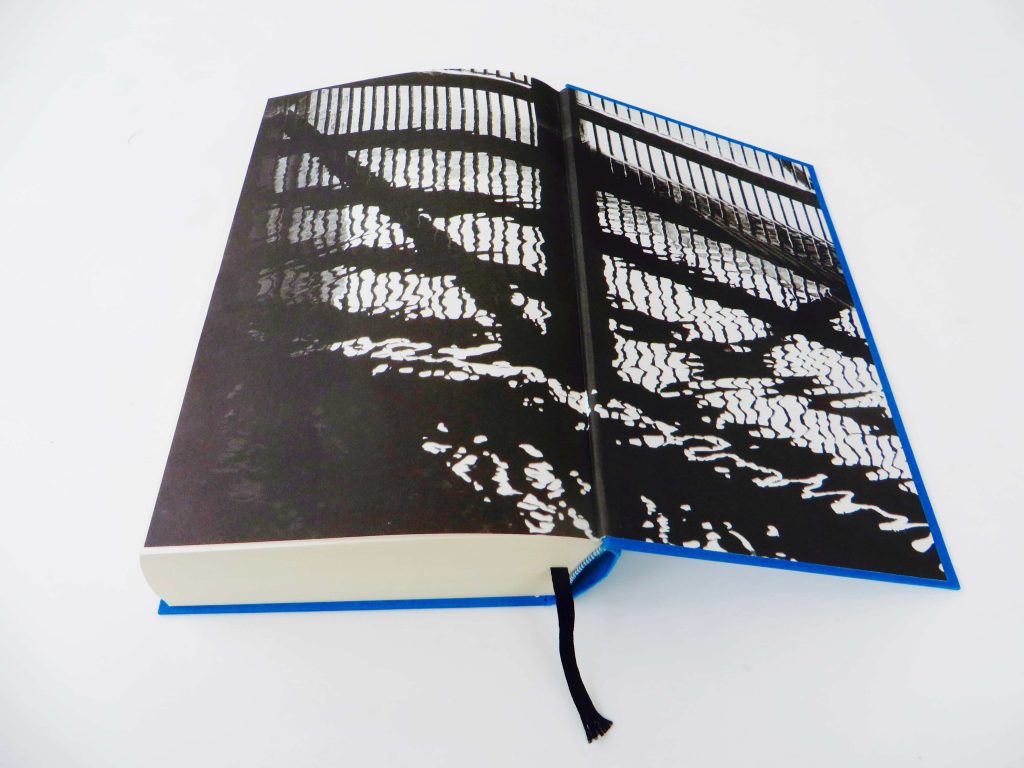

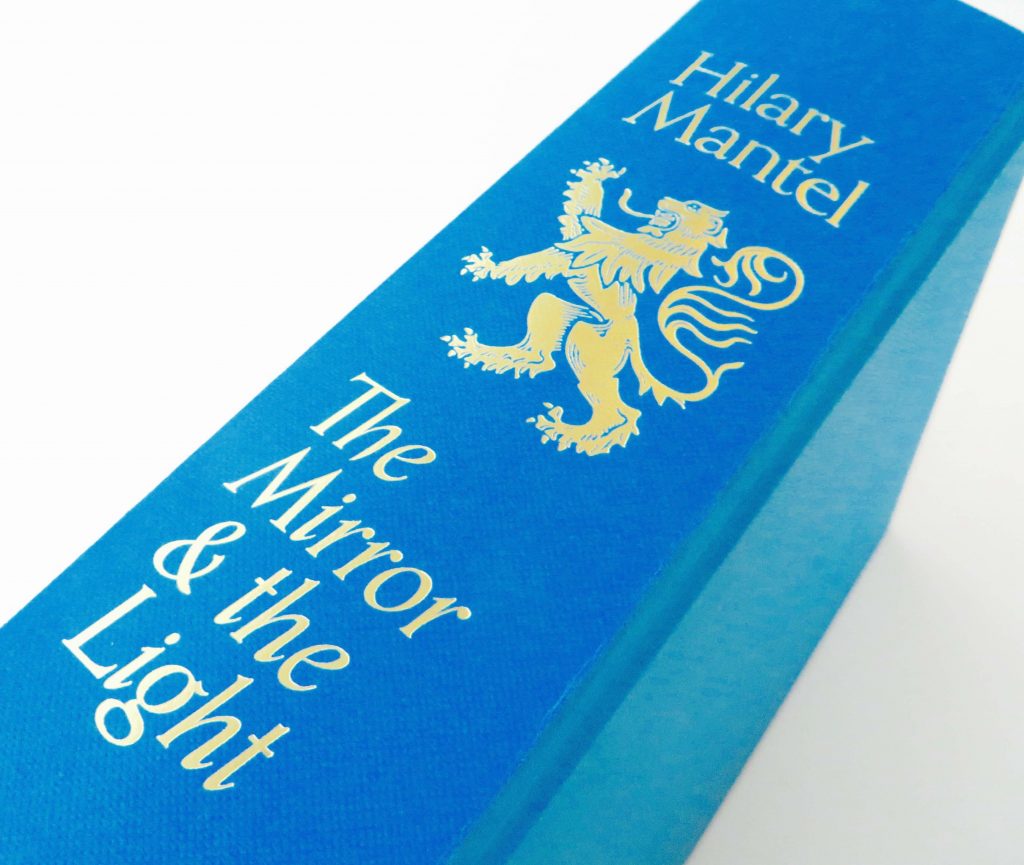

I’ve now finished the trilogy and I feel like a door has closed. The endpapers wrapping around ‘The Mirror & the Light’ show the sinister Traitor’s Gate at the Tower of London. I have survived the blood and guts of the Tudor Court and I realise we have a living genius in our midst. This is literature that will last. I am mesmerised, entranced – it is as if Hilary Mantel has gone back to Tudor times and, as an emissary, reported back to us in 2020. As Rachel Cooke in ‘The Observer’ noted about ‘Wolf Hall’ – ‘I loved ‘Wolf Hall’, but I was spooked by it too. The voice is so true: I have my suspicions that Hilary Mantel actually is Thomas Cromwell’.

Of ‘Bring Up The Bodies’, Jeremy Clarke of ‘The Spectator’ said ‘I am looking forward to being hideously spellbound once more’.

This is, (I hardly like to call it fiction), based on excellently researched historical fact. It’s like old footage of black and white films suddenly being transformed into colour and life. And then you realise that these people were just like us in their emotions, which often overcame common sense and led to ultimate disaster.

The religious and political bonds with the rest of Western Europe were both intimate and paramount in dictating how Henry VIII behaved both in war and in wives. ‘Catholics and Protestants alike hamstring politics, breed hatred, burn, torture, eviscerate, all in the name of God’ (Peter Green TLS).

Women were bartering tools, often used to gain wealth in land or possessions and not only with the king. If they could not produce a son and heir, they were usually got rid of – sometimes brutally. The Court was a lavish but dangerous place to inhabit – ‘ladies’ did not escape being beheaded too. Cromwell rose to be Henry’s Chief Advisor but he knew he walked a fine line, and would one day probably miss his footing.

When he is investigated for treason you look back in the book and see how threads are woven together to make trumped up charges stick – they are like fine silver and gold chains left to their own devices, hidden in a dark drawer, which tie themselves into knots and cannot be undone. As he became more and more powerful, the Lord Privy Seal failed to keep a sharp eye on his adversaries, some of whom he counted as ‘friends’. But would Cromwell have wanted to take over from Henry as Regent had the right circumstances arisen? I think so.

Cromwell was tough, acquisitive as befitting his position, promoting his family, all the while being aware of his aristocratic enemies who envied him and desired his downfall but he was also thoughtful, with a real eye for the beauty of the natural world and its seasons.

I walk down a street that I now know Thomas Cromwell would have walked down in the mid 1500s in London – and it’s a weird feeling. I’m on the look out for a flash of that orange coat, long gone but orange is still a favourite colour.

Colour, taste and smell infiltrate these characters, these places, the food, the small details of daily life in Tudor times. Hilary Mantel has created both a mega and micro world, which is totally immersive to the reader.

I can’t do better than recommend (again) reading the critics listed quotes at the beginning of the first two books. There is no point in me adding to these brilliant comments. Instead, I’m just going to put down a few descriptions which I found magical in ‘The Mirror & the Light’ and which will, I hope, encourage you to take up the 900 pages!

‘The king wears green velvet: he is a verdant lawn, starred with diamonds.’ He is young, fit and handsome.

Later on, when Henry has become obese and diseased … ‘The king’s beard bristles. He looks like a hog’s pudding about to burst its skin.’

‘In his (Cromwell’s) chamber the air is sharply scented: juniper, cinnamon. He takes off his orange coat’.

In the kitchens …

‘At his feet, eels are swimming in a pail, twisting and gliding; interlacing in their futile efforts, as they wait to be killed and sauced …..

The eels come in, presented in two fashions: salted in an almond sauce, and baked with the juice of an orange. There is a spinach tart, green as the summer evening, flavoured with nutmeg and a splash of rosewater. The silver gleams; the napkins are folded into the shapes of Tudor roses …’

This could also be an image of the Court – the rewards of the flesh, the riches to be gained, the honours to be had but all for a price – some may wriggle out of being beheaded but many will bear the fate of a cruel death before their time … or many years of imprisonment.

‘It is an aromatic custard in a white dish. He saw the gooseberries earlier, tiny bubbles of green glass, sour as a friar on a fast day. For this dish you need fresh hens’ eggs and a pitcher of cream; you need to be a prince of the church to afford the sugar……. The custard quakes in waves of sweetness and spice. ‘Nutmeg,’he says. ‘Mace. Cumin.’ ‘And rosewater.’

And with a final flourish, he freckles the cream with slivers of almonds and a drop or two of elderflower cordial.

Followed by sweet Venetian cakes, often made with ‘syrup of violets’.

Read page 164/5 just for the prose poetry of it.

There are small phrases – ‘a glance rinsed with rage’, ‘eyes like deep ponds on a still day’, ‘striated clouds like bales of silk’, ‘what maggots of ambition might be burrowing into the mind of the Duke of Norfolk’. An exquisite description of plums on page 681, fruits the size of a ‘baby’s heart’.

Cromwell reflecting on his youth, ‘scenting the staleness of soiled straw and stagnant water, the hot grease of the smithy, horse sweat, leather, grass, yeast, tallow, honey, wet dog, spilled beer, the lanes and wharves of his childhood’.

Hans Holbein is the Court painter. ‘In answer to his (Cromwell’s) summons, Master Holbein comes. He trails with him traces of his occupation: the scents of linseed and lavender oil, pine-resin and rabbit-skin glue’.

The Tudor Court is held up as a ‘dark mirror’ to our own world. We haven’t learned enough from mistakes made in the past. Or maybe Mantel’s ‘astonishing insight into human psychology (much of it extremely nasty)’ ( ‘The Spectator’) means we are not able to evolve as we should into a higher understanding of our place on the planet.

Just as the Traitor’s Gate endpapers enfold the book, so does the river Thames contain the city of London in its winding flow, the water reflecting times past and present, storm and calm, rain and sunlight, night and day.

…’so I won’t see August, he (Cromwell) thinks. The hares that flee the harvester, the cold morning dews after St Bartholomew’s Day. Or the leaf fall, the dark blue nights’ …

When Hilary Mantel had finished the final paragraphs of ‘The Mirror & the Light’ she went to bed and after a very disturbed night awoke to find that her print portrait of Henry VIII had fallen off her wall.

END